But Somehow I Knew I Would Never See Her or Paris Again

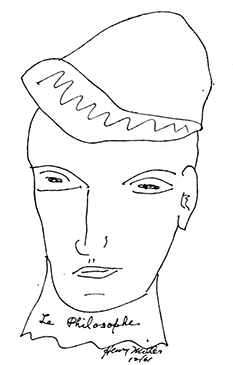

Henry Miller: Cocky portrait.

Henry Miller: Cocky portrait.

In 1934, Henry Miller, then anile forty-2 and living in Paris, published his commencement book. In 1961 the book was finally published in his native land, where it promptly became a best-seller and a cause célèbre. By now the waters take been and so muddied by controversy about censorship, pornography, and obscenity that one is probable to talk nearly anything simply the book itself.

But this is nothing new. Like D. H. Lawrence, Henry Miller has long been a byword and a legend. Championed by critics and artists, venerated by pilgrims, emulated by beatniks, he is to a higher place everything else a culture hero—or villain, to those who run into him equally a menace to law and order. He might fifty-fifty be described equally a folk hero: hobo, prophet, and exile, the Brooklyn male child who went to Paris when anybody else was going home, the starving bohemian enduring the plight of the creative artist in America, and in latter years the sage of Big Sur.

His life is all written out in a series of picaresque narratives in the first-person historical present: his early Brooklyn years inBlackness Spring, his struggles to find himself during the twenties inTropic of Capricorn and the iii volumes of theRosy Crucifixion, his adventures in Paris during the thirties inTropic of Cancer.

In 1939 he went to Hellenic republic to visit Lawrence Durrell; his sojourn there provides the narrative basis ofThe Colossus of Maroussi. Cut off past the state of war and forced to return to America, he fabricated the yearlong odyssey recorded inThe Air-Conditioned Nightmare. Then in 1944 he settled on a magnificent empty stretch of California coast, leading the life described inBig Sur and the Oranges of Hieronymus Bosch. Now that his name has made Large Sur a center for pilgrimage, he has been driven out and is once again on the move.

At seventy Henry Miller looks rather like a Buddhist monk who has swallowed a canary. He immediately impresses ane as a warm and humorous man. Despite his baldheaded head with its halo of white pilus, there is zippo old nigh him. His figure, surprisingly slight, is that of a young man; all his gestures and movements are young.

His voice is quite magically captivating, a mellow, resonant but quiet bass with great range and variety of modulation; he cannot be every bit unconscious as he seems of its musical spell. He speaks a modified Brooklynese frequently punctuated by such rhetorical pauses as "Don't you come across?" and "You know?" and trailing off with a series of diminishing reflective noises, "Yas, yas … hmm … hmm … yas … hm … hm." To get the total season and honesty of the man, 1 must hear the recordings of that voice.

The interview was conducted in September 1961, in London.

INTERVIEWER

First of all, would you lot explicate how y'all go about the actual business of writing? Exercise you sharpen pencils similar Hemingway, or anything like that to get the motor started?

HENRY MILLER

No, non more often than not, no, nothing of that sort. I generally go to work right after breakfast. I sit right downwards to the car. If I detect I'm not able to write, I quit. Simply no, at that place are no preparatory stages equally a rule.

INTERVIEWER

Are there certain times of 24-hour interval, sure days when you work meliorate than others?

MILLER

I prefer the morning now, and just for two or iii hours. In the beginning I used to work afterwards midnight until dawn, simply that was in the very beginning. Even after I got to Paris I constitute information technology was much better working in the forenoon. Simply then I used to piece of work long hours. I'd work in the morning, take a nap after dejeuner, become up and write once more, sometimes write until midnight. In the concluding ten or fifteen years, I've found that it isn't necessary to work that much. Information technology's bad, in fact. You drain the reservoir.

INTERVIEWER

Would yous say y'all write apace? Perlès said inMy Friend Henry Miller that you were ane of the fastest typists he knew.

MILLER

Yes, many people say that. I must make a great clatter when I write. I suppose I practise write rapidly. But so that varies. I can write rapidly for a while, then in that location come stages where I'm stuck, and I might spend an hr on a page. But that's rather rare, because when I find I'one thousand existence bogged down, I will skip a difficult part and go on, yous see, and come up back to it fresh another day.

INTERVIEWER

How long would you say it took yous to write one of your earlier books once you lot got going?

MILLER

I couldn't answer that. I could never predict how long a book would take: fifty-fifty now when I set out to do something I couldn't say. And information technology'south somewhat false to have the dates the author says he began and concluded a book. It doesn't mean that he was writing the book constantly during that time. TakeSexus,or accept the wholeRosy Crucifixion. I think I began that in 1940, and here I'1000 still on it. Well, it would be absurd to say that I've been working on it all this fourth dimension. I oasis't even idea about it for years at a fourth dimension. So how can you lot talk about information technology?

INTERVIEWER

Well, I know that you rewroteTropic of Cancer several times, and that work probably gave you more problem than any other, but of course information technology was the offset. And so too, I'm wondering if writing doesn't come up easier for you lot now?

MILLER

I think these questions are meaningless. What does it matter how long it takes to write a volume? If you were to inquire that of Simenon, he'd tell you very definitely. I think information technology takes him from iv to seven weeks. He knows that he can count on it. His books have a certain length usually. And so as well, he's one of those rare exceptions, a man who when he says, "At present I'm going to start and write this volume," gives himself to information technology completely. He barricades himself, he has zilch else to call back about or do. Well, my life has never been that mode. I've got everything else under the sunday to do while writing.

INTERVIEWER

Do you edit or alter much?

MILLER

That also varies a swell deal. I never do any correcting or revising while in the process of writing. Let's say I write a matter out any quondam way, so, after information technology'due south cooled off—I let it rest for a while, a month or two peradventure—I see it with a fresh eye. Then I take a wonderful time of it. I simply go to work on it with the ax. But not always. Sometimes it comes out about similar I wanted it.

INTERVIEWER

How practice you get about revising?

MILLER

When I'grand revising, I utilize a pen and ink to make changes, cross out, insert. The manuscript looks wonderful later on, like a Balzac. Then I retype, and in the process of retyping I brand more than changes. I prefer to retype everything myself, considering fifty-fifty when I recollect I've fabricated all the changes I desire, the mere mechanical business of touching the keys sharpens my thoughts, and I notice myself revising while doing the finished thing.

INTERVIEWER

Yous mean there is something going on between you and the machine?

MILLER

Yes, in a way the machine acts as a stimulus; information technology's a cooperative thing.

INTERVIEWER

InThe Books in My Life, yous say that most writers and painters work in an uncomfortable position. Exercise you call back this helps?

MILLER

I do. Somehow I've come to believe that the last thing a writer or any artist thinks well-nigh is to make himself comfy while he's working. Perhaps thediscomfort is a bit of an assist or stimulus. Men who can afford to work nether better conditions often cull to work under miserable conditions.

INTERVIEWER

Aren't these discomforts sometimes psychological? Yous take the example of Dostoyevsky …

MILLER

Well, I don't know. I know Dostoyevsky was always in a miserable state, but yous can't say he deliberately chose psychological discomforts. No, I dubiety that strongly. I don't call up anyone chooses these things, unless unconsciously. I practise think many writers have what you might phone call a demonic nature. They are always in trouble, you know, and not simply while they're writing or because they're writing, but in every aspect of their lives, with marriage, love, business, money, everything. It's all tied together, all part and package of the same matter. It'due south an attribute of the creative personality. Not all creative personalities are this manner, but some are.

Source: https://www.theparisreview.org/interviews/4597/the-art-of-fiction-no-28-henry-miller

0 Response to "But Somehow I Knew I Would Never See Her or Paris Again"

Post a Comment